It’s Sunday! Did You Know…

* 1815 – Treaty of Ghent Proclaimed in Washington – ending the War of 1812.

The Treaty of Ghent was the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812 between the United States of America and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Both sides signed it on December 24, 1814, in the city of Ghent, Belgium. The treaty restored relations between the two nations to status quo ante bellum, restoring the borders of the two countries to the lines before the war started in June 1812. The Treaty was approved by the UK parliament and signed into law by the Prince Regent (the future King George IV) on December 30, 1814. It took a month for news of the peace treaty to reach the United States, and in the meantime, American forces under Andrew Jackson won the Battle of New Orleans on January 8, 1815. The Treaty of Ghent was not fully in effect until it was ratified by the U.S. Senate unanimously on February 17, 1815. It began two centuries of peaceful relations between the U.S. and Britain, although there were a few tense moments such as the Trent Affair.

At last in August 1814, peace discussions began in the neutral city of Ghent. As the peace talks opened American diplomats decided not to present President Madison’s demands for the end of impressment and suggestion that Britain turns Canada over to the U.S. They were quiet and instead the British opened with their demands, chief of which was the creation of an Indian barrier state in the American Northwest Territory (the area from Ohio to Wisconsin). It was understood the British would sponsor this Indian state. The British strategy for decades had been to create a buffer state to block American expansion. The Americans refused to consider a buffer state and the proposal was dropped. Article IX of the treaty included provisions to restore to Natives “…all possessions, rights, and privileges which they may have enjoyed, or been entitled to in 1811″—but the provisions were unenforceable, and in any case, Britain stopped supporting or encouraging tribes in American territory.

The British, assuming their planned invasion of New York state would go well, also demanded that Americans not have any naval forces on the Great Lakes and that the British get certain transit rights to the Mississippi River in exchange for continuation of American fishing rights off Newfoundland. The U.S. rejected the demands and there was an impasse. American public opinion was so outraged when Madison published the demands that even the Federalists were willing to fight on.

During the negotiations, the British had four invasions underway. One force carried out a burning of Washington, but the main mission failed in its goal of capturing Baltimore. The British fleet sailed away when the army commander was killed. A small force invaded the District of Maine from New Brunswick, capturing parts of northeastern Maine and several smuggling towns on the seacoast. Much more important were two major invasions. In northern New York State, 10,000 British troops marched south to cut off New England until a decisive defeat at the Battle of Plattsburgh forced them back to Canada. The defeat was a humiliation that called for a court-martial of the commander. Nothing was known at the time of the fate of the other major invasion force that had been sent to capture New Orleans and control the Mississippi River.

After months of negotiations, against the background of changing military victories, defeats, and losses, the parties finally realized that their nations wanted peace and there was no real reason to continue the war. Each side was tired of the war. Export trade was all but paralyzed, and after the fall of Napoleon in 1814, France was no longer an enemy of Britain, so the Royal Navy no longer needed to stop American shipments to France and no longer needed more seamen. The British were preoccupied in rebuilding Europe after the apparent final defeat of Napoleon. Lord Liverpool told British negotiators to offer a status quo, which the British government had desired since the beginning of the war. British diplomats immediately offered this to the US negotiators, who dropped demands for an end to British maritime practices and Canadian territory (ignoring their war aims) and agreed. The sides would exchange prisoners, and Britain would return or pay for slaves captured from the United States.

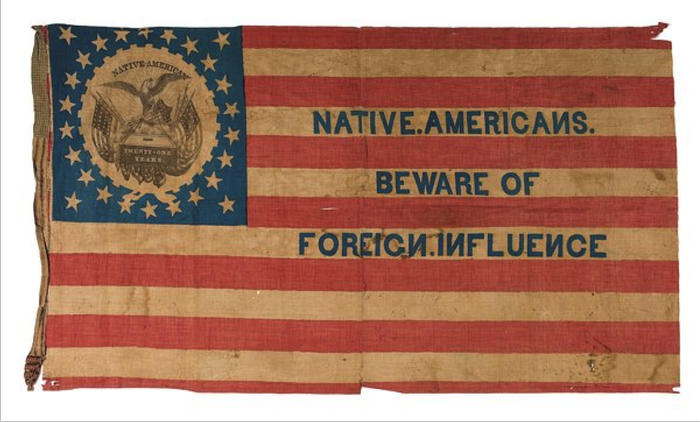

* 1856 Know-Nothings convene in Philadelphia

The American Party, also known as the “Known-Nothing Party,” convenes in Philadelphia to nominate its first presidential candidate.

The Know-Nothing movement began in the 1840s when an increasing rate of immigration led to the formation of a number of so-called nativist societies to combat “foreign” influences in American society. Roman Catholic immigrants from Ireland and Italy, who were embraced by the Democratic Party in eastern cities, were especially targeted. In the early 1850s, several secret nativist societies were formed, of which the “Order of the Star-Spangled Banner” and the “Order of United Americans” were the most significant. When members of these organizations were questioned by the press about their political platform, they would often reply they knew nothing, hence the popular name for the Know-Nothing movement.

In 1854, the Know-Nothings allied themselves with a faction of Whigs and ran for office in several states, calling for legislation to prevent immigrants from holding public office. By 1855, support for the Know-Nothings had expanded considerably, and the American Party was officially formed. In the same year, however, Southerners in the party sought to adopt a resolution calling for the protection of slavery, and some anti-slavery Know-Nothings defected to the newly formed Republican Party.

On February 18, 1856, the American Party met to nominate its first presidential candidate and to formally abolish the secret character of the organization. Former president Millard Fillmore of New York was chosen, with Andrew Donelson of Tennessee to serve as his running mate. In the subsequent election, Fillmore succeeded in capturing only the state of Maryland, and the Know-Nothing movement effectively ceased to exist.

* 1930 Pluto discovered

Pluto, once believed to be the ninth planet, is discovered at the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, by astronomer Clyde W. Tombaugh.

The existence of an unknown ninth planet was first proposed by Percival Lowell, who theorized that wobbles in the orbits of Uranus and Neptune were caused by the gravitational pull of an unknown planetary body. Lowell calculated the approximate location of the hypothesized ninth planet and searched for more than a decade without success. However, in 1929, using the calculations of Powell and W.H. Pickering as a guide, the search for Pluto was resumed at the Lowell Observatory in Arizona. On February 18, 1930, Tombaugh discovered the tiny, distant planet by use of a new astronomic technique of photographic plates combined with a blink microscope. His finding was confirmed by several other astronomers, and on March 13, 1930–the anniversary of Lowell’s birth and of William Hershel’s discovery of Uranus–the discovery of Pluto was publicly announced.

With a surface temperature estimated at approximately -360 Fahrenheit, Pluto was appropriately given the Roman name for the god of the underworld in Greek mythology. Pluto’s average distance from the sun is nearly four billion miles, and it takes approximately 248 years to complete one orbit. It also has the most elliptical and tilted orbit of any planet, and at its closest point to the sun it passes inside the orbit of Neptune, the eighth planet.

After its discovery, some astronomers questioned whether Pluto had sufficient mass to affect the orbits of Uranus and Neptune. In 1978, James Christy and Robert Harrington discovered Pluto’s only known moon, Charon, which was determined to have a diameter of 737 miles to Pluto’s 1,428 miles. Together, it was thought that Pluto and Charon formed a double-planet system, which was of ample enough mass to cause wobbles in Uranus’ and Neptune’s orbits. In August 2006, however, the International Astronomical Union announced that Pluto would no longer be considered a planet, due to new rules that said planets must “clear the neighborhood around its orbit.” Since Pluto’s oblong orbit overlaps that of Neptune, it was disqualified.

* 1948 De Valera resigns

After 16 years as head of independent Ireland, Eamon de Valera steps down as the Taoiseach, or Irish prime minister, after his Fianna Fail Party fails to win a majority in the Dail Eireann (the Irish assembly). As a result of the general election, the Fianna Fail won 68 of the 147 seats in the Dail, and de Valera resigned rather than lead a coalition government. In his place, John A. Costello, leader of the Fine Gael Party, joins with several smaller groups to achieve a majority and becomes Irish prime minister.

Eamon de Valera, the most dominant Irish political figure of the 20th century, was born in New York City in 1882, the son of a Spanish father and Irish mother. When his father died two years later, he was sent to live with his mother’s family in County Limerick, Ireland. He attended the Royal University in Dublin and became an important figure in the Irish-language revival movement.

In 1913, he joined the Irish Volunteers, a militant group that advocated Ireland’s independence from Britain, and in 1916 participated in the Easter Rising against the British in Dublin. He was the last Irish rebel leader to surrender and was saved from execution because of his American birth. Imprisoned, he was released in 1917 under a general amnesty and became president of the nationalist Sinn Fein Party. In May 1918, he was deported to England and imprisoned again, and in December Sinn Fein won an Irish national election, making him the unofficial leader of Ireland.

In February 1919, he escaped from jail and fled to the United States, where he raised funds for the Irish Republican movement. When he returned to Ireland in 1920, Sinn Fein and the Irish Republican Army (IRA) were engaged in a widespread and effective guerrilla campaign against British forces.

In 1921, a truce was declared, and in 1922 Arthur Griffith and other former Sinn Fein leaders broke with de Valera and signed a treaty with Britain, which called for the partition of Ireland, with the south becoming autonomous and the six northern counties of the island remaining part of the United Kingdom. In the period of civil war that followed, de Valera supported the Republicans against the Irish Free State (the new government of the autonomous south) and was imprisoned by William Cosgrave’s Irish Free State ministry.

In 1924, he was released and two years later left Sinn Fein, which had become the unofficial political wing of the underground movement for northern independence. He formed Fianna Fail, and in 1932 the party gained control of the Dail Eireann and de Valera became Irish prime minister.

For the next 16 years, de Valera pursued a policy of political separation from Great Britain, including the introduction of a new constitution in 1937 that declared Ireland the fully sovereign state of Eire. During World War II, he maintained a policy of neutrality but repressed anti-British intrigues within the IRA.

In 1948, he narrowly lost re-election due to a negative public reaction against his party’s long monopoly of power. Out of office, he toured the world advocating the unification and independence of Ireland. His successor as Taoiseach, John Costello, officially made Ireland an independent republic in 1949 but nonetheless lost the prime minister’s office to de Valera in the 1951 election. The relative Irish economic prosperity of the 1940s declined in the 1950s, and Costello began a second ministry in 1954, only to be replaced again by de Valera in 1957.

In 1959, de Valera resigned as prime minister and was elected Irish president–a largely ceremonial post. On June 24, 1973, de Valera, then the world’s oldest head of state, retired from Irish politics at the age of 90. He passed away two years later.

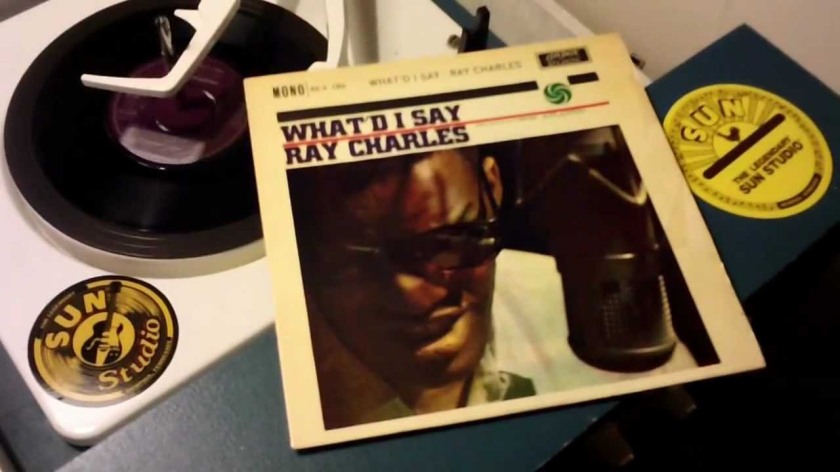

* 1959 Ray Charles records “What’d I Say” at Atlantic Records

The phone call that Ray Charles placed to Atlantic Records in early 1959 went something like this: “I’m playing a song out here on the road, and I don’t know what it is—it’s just a song I made up, but the people are just going wild every time we play it, and I think we ought to record it.” The song Ray Charles was referring to was “What’d I Say,” which went on to become one of the greatest rhythm-and-blues records ever made. Composed spontaneously out of sheer showbiz necessity, “What’d I Say” was laid down on tape on this day in 1959, at the Atlantic Records studios in New York City.

The necessity that drove Ray Charles to invent “What’d I Say” was simple: the need to fill time. Ten or 12 minutes before the end of a contractually required four-hour performance at a dance in Pittsburgh one night, Charles and his band ran completely out of songs to play. “So I began noodling—just a little riff that floated into my head,” Charles explained many years later. “One thing led to another and I found myself singing and wanting the girls to repeat after me….Then I could feel the whole room bouncing and shaking and carrying on something fierce.”

What was it about “What’d I Say” that so captivated the audience at the Pittsburgh dance that night and the rest of humanity ever since then? Charles always thought it was the sound of his Wurlitzer electric piano, a very unfamiliar instrument at the time. Others would say it was the call-and-response in the song’s bridge—all unnnhs and ooohs and other sounds not typically found on the average pop record of 1959. Whatever it was, it worked well enough to become Charles’ closing number from that night in Pittsburgh until his final show.

“You start ‘em off, you get ‘em just first tapping their feet. Next thing they got their hands goin’, and next thing they got their mouth open and they’re yelling, and they’re singin’ and they’re screamin’. It’s a great feeling when you got your audience involved with you.”

“What’d I Say” was a sure-fire hit with live audiences and with record-buyers. It was a #1 R&B hit for Ray Charles in 1959 and a #6 pop hit as well—his first bona fide crossover hit, but certainly not his last.

Today’s Sources:

* Canadian History Timeline – Canada’s Historical Chronology http://canadachannel.ca/todayincanadianhistory/index.php

* This Day In History – What Happened Today http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/

* Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Treaty_of_Ghent

Interesting about the know nothing party. Ray Charles was omnipresent at all our college functions. We loved to do the oooo uhhhhhhhh parts along with him.

LikeLiked by 1 person

We had fun back in the day, eh! That ugly thinking of the know nothing Party rears it’s head from time to time. It seems that Trump has brought out the worst in the country.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Seems that way, doesn’t it?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Indeed he has. Hopefully, Mueller is closing in.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ray Charles’ What’d I Say is a classic. Who can hear it and not want to join with song or dance? Thank you for the reminder. Wow. Love it! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad I found a favorite for you! Thanks, Gwen!

LikeLike

The “Know-Nothings” – what a success story… not!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Exactly! I daresay that had they been successful, America’s economic development would have been seriously stunted. Thanks, Bob.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great Ray Charles story. Love the Jackie Kennedy photo. I had not heard of the Know Nothing Party. Very interesting. Thanks, John.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I had forgotten about the Know Nothings until I saw this event – I remembered from the days when I taught US history. Thanks, Jennie!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank YOU, John!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well I have never heard of the Know Nothing Party or the American Party – you live and learn.

That Ray Charles track was fabulous wasn’t it?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, Ray Charles was a very gifted person. I chose that piece about the Know-Nothings/American Party because it shows that immigration has been a contentious issue in US politics for a long time. At the bottom of that kind of thinking in any Western nation is the old belief in White Supremacy and English ethnocentrism. Thanks, Opher.

LikeLike